I did not plan this. There was no long vision, no defined goal. I never wrote a 10-year plan. I remember sitting in the cramped office of my high school guidance counselor and confessing that, thanks to less than perfect eyesight and some abysmal math scores scuttling my statistically near impossible dreams of becoming a fighter pilot, I couldn’t really think of anything that I wanted to pursue as a career.

Two years later, after a busy phase of working at a video game/ice cream parlor, pumping gas at the Mobil station in Waihi, and punching the clock at my dad’s helmet factory, I found myself in California on the other end of a one way plane ticket with a place to live and a job crushing grapes at Page Mill Winery. The logic I had used to support this move was that California was a better place to study journalism than New Zealand because the post-college opportunities were more widespread. What followed was a spectacular period of failing to really apply myself diligently to anything. I worked as a construction grunt, a video store counter geek, a swing shift prep cook at an industrial kitchen, a fitness instructor (ha!), a tree service stump grinder, and puttered around a few bay area junior colleges. By the time I had met the requirements to transfer to a four year college I was about three years older than my peers and would show up for class at SFSU smelling richly of whatever the stump du jour had showered me with.

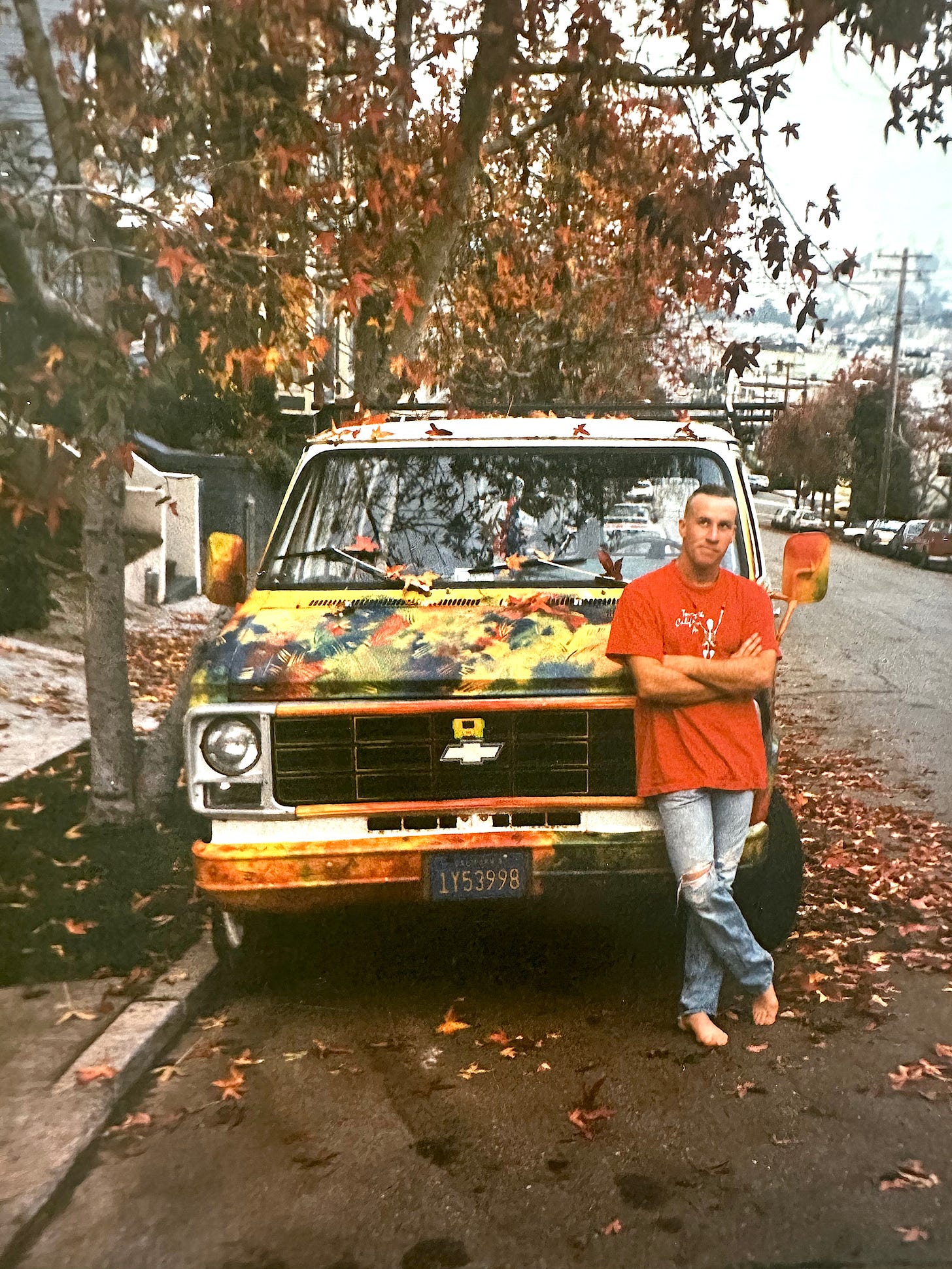

Ahhh, sweet bird of youth… All dressed up and no place to go. Although, in this case, I think there was a bike and a couch in the back of the van, and we were headed to Mammoth. 1988? 1989?

The only thing that I had really applied myself to during that three-year odyssey of struggle-bussing out of teenage had been mountain biking. I had fallen for them in 1985, and by the time I was living in San Francisco there was really nothing I wanted to do but ride bikes, race bikes, and wrench on bikes. So, it made some sort of roundabout sense (to me, anyway. I suspect my parents were experiencing a colossal wave of “What the everloving fuck is he doing now?”) to drop out of college and go to work at Velo City on Stanyan Street for five bucks an hour. 1988. Holland Jones R.I.P, and thank you for that start. Velo City was a perfect place to get initiated into the mysteries of cycling, and the crew there was entirely over-educated and under-employed. They were fantastic human beings who dipped me in every aspect of cycling from all-day rides on Tam to late night derbies in laundromats and moonlit missions throughout the city. And they taught me how to work on bikes.

During the prior meandering through just about every creative writing course on tap at Foothill College and the College of San Mateo (The Gateway To Achievement!) I had lost count of the number of times we would be told as a class that “in all likelihood, none of you will ever get published”. I had also decided that I wasn’t really cut out for journalism. So, onward and upward into the wildly lucrative and opportunity filled world of bicycle mechanics!

A couple years later I was working at Seal Rock Cycles, having been lured over there by my riding buddy Mitch Bramlett. Seal Rock was way out in the Avenues, 28th and Geary, and the summer weather was the kind of windswept grey brutality that Mark Twain wrote about. It was run by this comedic Wildman named Earl Cotter (also R.I.P, man, what a force of life he was), who at the time was completely addicted to windsurfing. He’d leave in the morning if the wind forecast was looking good at Chrissy Field, and would return all salt crusted at the end of the day, look at the whopping $300 of business we had done, sigh, and say that at least it had been howling at Chrissy. I wasn’t too surprised when he had to lay me off one exceptionally foggy August day.

Fortunately my friend Henry Kingman was working at this free paper called California Bicyclist; he mentioned that their receptionist was in her third trimester and they needed someone to come in and answer the phones in the mornings. So I did. This was when writers would fax their stories in, and usually follow the fax up with a phone call. I found myself on the phone with Joe Glydon and Maynard Hershon, and we would shoot the shit about bikes and writing. At some point the publisher was walking past and overheard me. “Do you know how to write?”

Busted! I answered in the affirmative, worried that I had violated some unrealized code of ethics for phone jockeys. Instead, I found myself (probably with some influence from Henry) being asked to go do a ride called “White Mountain Peak In A Day” and write about it. Ten cents a word!

That’s where all this started. Earl hired me back at Seal Rock, Mitch kicked my ass all over the headlands on training rides then moved to Santa Cruz to go work at The Bike Trip. I began writing a regular column about mountain bike racing in California Bicyclist, called “Knob-O-Rama”, then added in an anonymously penned advice column titled “Mr Surlywrench”, then moved to Santa Cruz to follow Mitch to The Bike Trip. California Bicyclist, meanwhile, started really having some fun with editorial content – first with Henry at the helm, then with Chip Baker. They were never afraid to shake things up, and had the kind of slightly loose, devil may care attitude that comes with ten-cent-a-word pay rates. We weren’t in it for the money, and we weren’t too concerned about getting called to the mat for stepping over the line. As such, we churned out some awesome stuff.

Some of that awesome stuff was mine. So was some of the not so awesome stuff, but I was learning. This led to writing for Winning magazine, and getting schooled by Rich Carlson (also R.I.P. So many of my mentors have left the building. That, in part, is why I am trying to get all these columns compiled here) on the nuts and bolts of structured journalism.

At some point, it dawned on me that I was developing a portfolio. I tried to leverage that and get a job at Bicycling. At the time, Bicycling was the absolute zenith of cycling publications. It had the biggest circulation, and the highest ad rates, and Rodale Publishing paid its editors real well. There was an office in Soquel, practically in Santa Cruz. Rodale was about to relaunch Mountain Bike magazine, and I had enough of a chip on my shoulder to think I could run that gig. I realize now how incredibly naïve that assumption was, and am thankful to this day that that I got passed over in favor of Dan Koeppel (who was and still is a hell of a writer) and Zapata Espinoza (who was far more editorially experienced and connected, in addition to being a whole lot more serious and grown up than I was).

I didn’t mind. I had a job at an awesome bike shop, was making at least twelve cents a word at California Bicyclist and even more over at Winning whenever their Belgian publisher remembered to pay me, was immersed completely in a red hot riding and racing scene, and felt, maybe for the first time in my life, like I was really part of something.

Somewhere in Octoberish of 1993, I attended this trade show called BIO. BIO stood for Bicycle Industry Organization, I think, and popped up as a play by some of the mega-brands to try and compete with Interbike. It only lasted two years, but was an excuse for shop rats and struggling journalists looking to shake down their Belgian publishers for back pay to head to Las Vegas. It was there, on the last day of the show, still high from a few hits of incredibly good liquid LSD the night before, having successfully made a Belgian publisher uncomfortable enough to ensure promise of payment, that I heard there were these guys walking around the show talking about a new magazine they were planning on launching. Never met them, returned to Santa Cruz wondering if I had just missed my date with destiny.

Rob Story called a couple weeks later. He was the managing editor of the aforementioned magazine, as well as Powder magazine. He assured that it hadn’t been the acid messing with my head; there was going to be a new magazine put out by the people who published Powder and Surfer, and it was going to be entirely mountain bike focused, photo heavy, and “different.” He had read a piece I had written in California Bicyclist about road tripping to the Cactus Cup in a VW bus with a keg of beer, and was wondering if maybe I wanted to write a story about road trips for the first issue of this new magazine. Fuck yes I did.

We talked some more, and he mentioned that they felt like this new magazine needed a regular column, something gritty, written by someone who was neck deep in it, maybe from a bike mechanic’s perspective. I said something about grit under the fingernails. He said something about shooting from the hip, the front of the book, setting the tone, greeting the readers from somewhere real. I said something like a handshake. He said yeah. I said, “like a grimy handshake?” We both paused a second, then we started laughing at the same time. The magazine was gonna be called BIKE.

And there we went.

My entire life has been one long trust fall with the universe. Like I said, I didn’t plan this. Planning has never been my strong suit, and there have been times when that has felt like a curse, and others when that has manifested as my secret superpower. Somehow, that trust fall with fate led to twenty seven years of Grimy Handshake columns. Amazing adventures were had along the way, along with plenty of white knuckling through life without any sort of safety net. I was incredibly lucky to be where I was, when I was, and to have the opportunity to follow this two-wheeled muse for as long as I have.

Thanks for coming on the ride. Then and now.